Quality

The Swiss Army Knife of Manufacturing

June 22, 2020

Move over rubber. Here comes thermoplastic elastomer, the squishy, stretchy, and superbly strong class of polymers that’s good for everything from weather stripping to sleep apnea masks to handles on power tools. Thermoplastics and, more broadly, polymers play an important role in our everyday lives. See our previous blog post, Materials Monday: Polymers on Parade, for our introduction to this ubiquitous material. Imagine a world without Legos (made of acrylonitrile butadiene styrene, a.k.a. ABS), Wiffle Balls (polyurethane), or Flexible Flyer sleds (high-density polyethylene). What would we do to stay entertained on weekends? We’ve also talked about the two main types of thermoplastics with our blogs on amorphous and semicrystalline polymers (See those blogs at Materials Monday: All About Amorphous and Materials Monday: A Semi-crystalline Synopsis).

Six classes of TPE exist, which we’ll discuss in a moment, but for now, know that TPE is what chemistry geeks call a copolymer—a polymer made of two or more monomers, just like ABS, polyvinyl chloride (PVC), and good old polytetrafluoroethylene, better known as Teflon. Unlike those other copolymers, however, TPE has the upper hand in several areas, providing a best of all worlds combination of flexibility, mechanical strength, absence of creep under load (unlike Teflon), and excellent resistance to wear, solvents, and heat. It’s also recyclable and simpler to process than the alternative, vulcanized rubber.

It’s these last two factors, in fact, that help explain TPE’s rising popularity in the automotive, consumer electronics, industrial machinery, and medical industries (some TPEs are also biocompatible). Because of this, TPE and its brethren are found in everything from weather stripping to sleep apnea masks to handles on power tools. TPE rocks.

Rubber has a slight edge over TPE in high heat applications—depending on the type, TPE begins to melt at 340°F or so, while natural rubber holds the line up to 356°F and silicone rubber (which is not actually rubber at all but rather a synthetic elastomer) takes the thermal resistance prize with an 842°F melting point. Vulcanized rubber, on the other hand, doesn’t melt at all—it catches fire instead, an alarming event that is outright dangerous and therefore prevents its use in many applications.

Rubber also has a price advantage, so it’s unlikely you’ll ever see TPE tires on your car, fire risk notwithstanding. Where you will see TPE used is in any plastic injection molding application calling for extreme performance, recyclability, and versatility, and where the faster processing speeds of TPE over thermosetting rubber outweigh its higher material cost. One of the most exciting design uses of TPE is for overmolding. The soft, squishy handle on your power drill is most likely made of overmolded TPE, as is that of your toothbrush, disposable razor, and practically any other plastic injection molded product requiring an ergonomic, slip-proof grip. TPE can also be used with fused filament fabrication (a popular type of 3D printing) as well as extrusion, blow molding, and thermoforming.

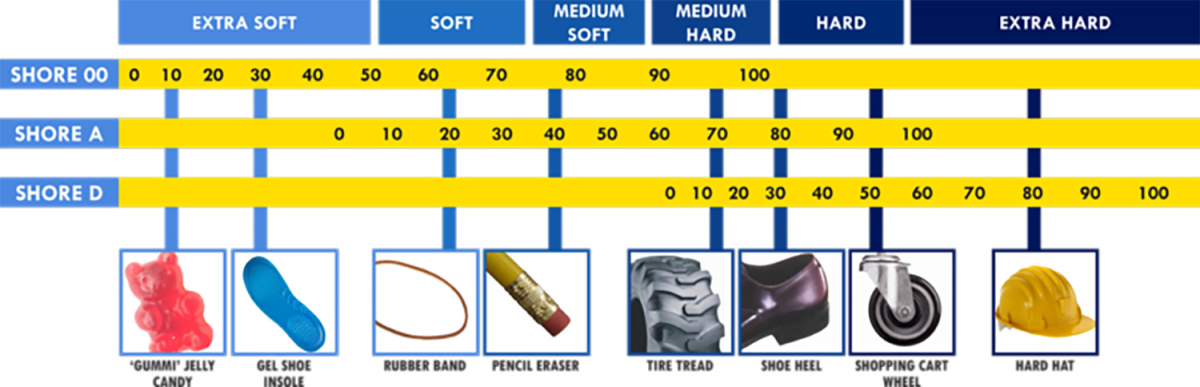

In closing, you can think of TPE as the “new rubber” (even though it’s been around longer than the automobile), but one that’s recyclable and much easier to fabricate into a practically infinite variety of products. As noted, TPE can be a bit more expensive than rubber, but given the fact that it’s faster and simpler to process, any delta in material cost is offset by its greater manufacturability. TPE can be hard like a hockey puck or possess nearly gel-like flexibility, is suitable for temperatures from the Antarctic to the Saharan desert, and resists tearing, chemical attack, oils and electricity. Feel like chatting more about TPE and all its variants? You know where to find us.

If you'd like to know more, pick up the phone and call us at (630) 592-4515 or email us at sales@prismier.com. Or if you're ready for a quote, email quotes@prismier.com. We'll be happy to discuss your options.