Quality

The Swiss Army Knife of Manufacturing

June 22, 2020

The Matchbox cars and Monopoly game pieces you might have played with as a kid are die cast. So are most engine blocks, transmission housings, cylinder heads, and alternator bodies. Beyond the automotive sector, many plumbing components are die cast, as are laptop computer frames, toaster and blender bases, along with a whole slug of components for the medical, communication, electrical, and firearm industries. Die cast parts are everywhere.

Most such parts are made of “white metals” such as zinc, aluminum, or magnesium, although copper and bronze can also be die cast. Ferrous materials like iron and steel, on the other hand, are found in traditional mold-based casting processes. White metals are preferred for their low melting points, corrosion resistance, and high strength to weight ratios, making them ideal for applications where light weight is a priority.

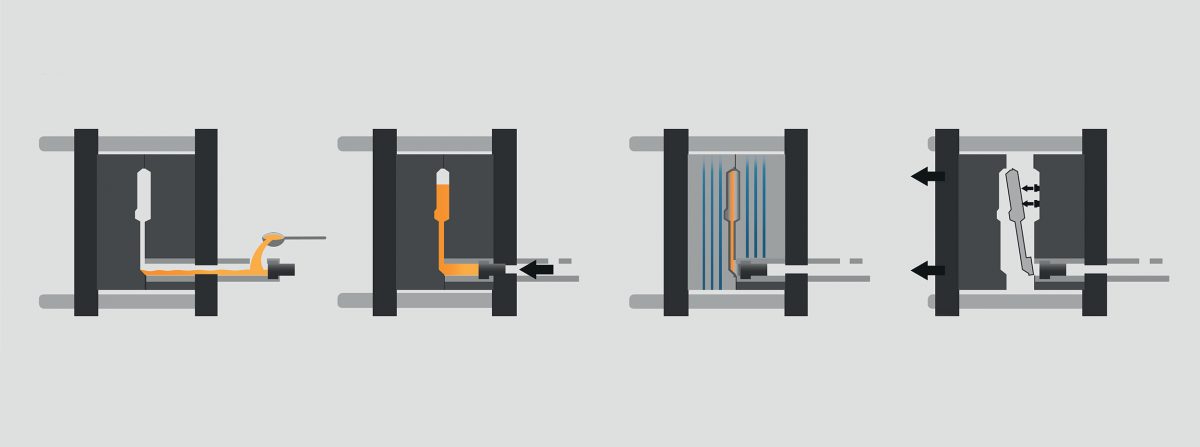

Cold chamber die casting machines, on the other hand, rely on a ladle to fill the cylinder with molten material. This additional step makes it slower than hot chamber die casting, but because the injection mechanism is not constantly immersed in extremely hot liquid metal, cold chamber machines support the casting of aluminum and other metals with higher melting temperatures. There are also a number of variants and proprietary systems available, such as low-pressure and vacuum die casting, squeeze casting, and die casting using multiple slides for high complexity parts.

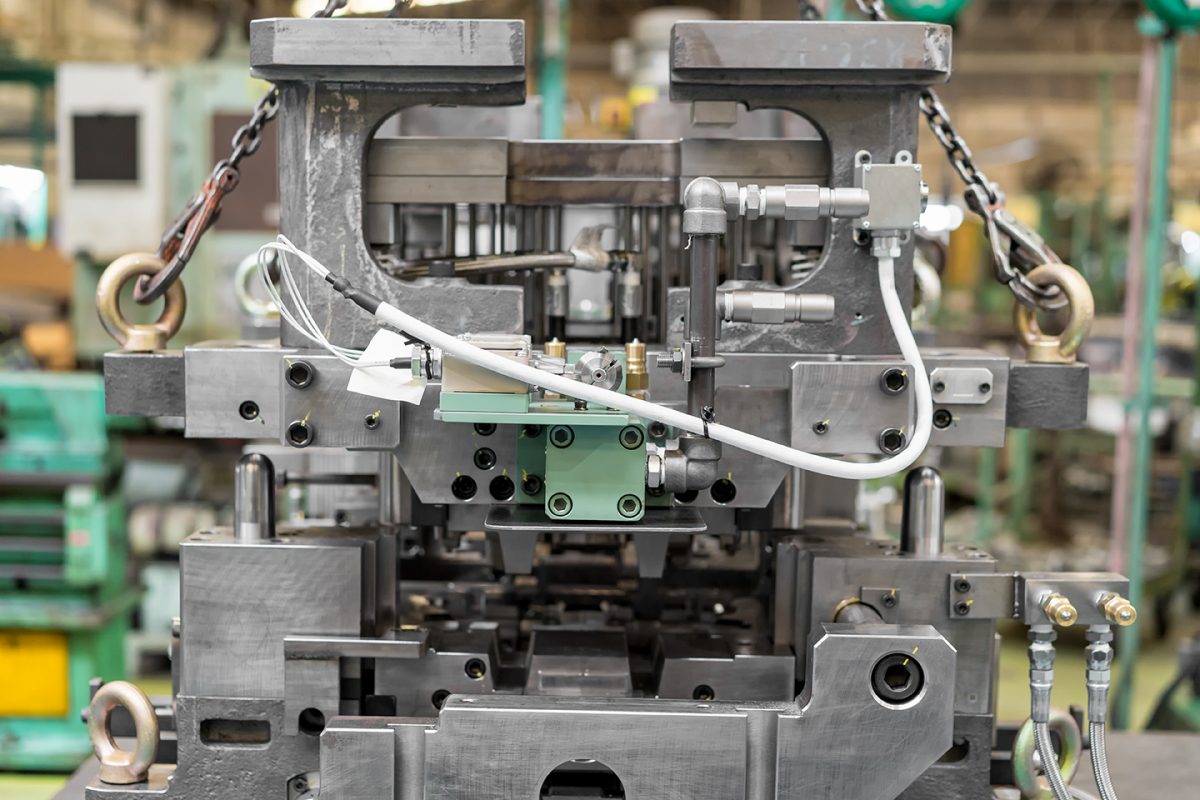

Note the term “deflash” just mentioned. As discussed earlier, the tool used to make die cast parts—the die, sometimes referred to as a mold—is constructed of two halves, and contains runners and sprues through which the molten material flows. When the casting cycle ends, the die’s movable half retracts, and ejector pins within force the finished part and its attached runners from the die. These must be removed and the adjoining surfaces smoothed, usually with a trim die or even a hand tool to cut away the runners before sanding the rough edges with an abrasive belt.

Deflashing aside, even the most perfectly machined die surfaces can allow some small amount of material to escape between the two when subjected to the intense pressures of the die casting process. These are called parting lines. The same phenomena occur with cast metal parts and ones made using plastic injection molding, but as with die casting, all can be minimized through the use of a well-designed, high-quality die and proper application of casting parameters such as metal temperature, pressure, and flow. Whatever the process, parting lines are common and must be removed using mechanical means if cosmetics are important.

These and other best practices are known as Design For Manufacturability, or DFM. Anyone responsible for the procurement of die cast parts should at least be familiar with the basics of DFM; those of you tasked with designing them should absolutely have a firm grasp of these principles. If not, poor part quality, high costs, and development missteps are sure to occur.

Another thing these people should know is the capabilities of their potential supplier. Often considered a high-volume affair, die casting can, however, be cost-effective even in very small quantities. This is known as rapid die casting. Some manufacturing companies (Prismier is one) are able to produce dies and molds suitable for prototype use, giving designers a fast, easy way to develop parts without heavy tooling investment, and then scale up as their products move into higher volumes. If you’d like to hear more about the rapid die casting process or get some advice on DFM in general, send us an email or pick up the phone.

If you'd like to know more, pick up the phone and call us at (630) 592-4515 or email us at sales@prismier.com. Or if you're ready for a quote, email quotes@prismier.com. We'll be happy to discuss your options.