Quality

The Swiss Army Knife of Manufacturing

June 22, 2020

We promised not to leave you hanging on the second half of the amorphous vs. semi-crystalline thermoplastic polymers discussion, and we meant it. That previous post, Materials Monday: Amorphous Thermoplastics, was a fun read, to be sure, so feel free to cruise on back to that if you missed the chance to dig into the details of polymeric structures and transition temperatures. We also have additional resources for each thermoplastic subcategory with our Amorphous Thermoplastics datasheet and our Semicrystalline Thermoplastics datasheet. You might also be interested in our blogs on injection molding which describe the processes of plastic injection molding and rapid injection molding.

Today, though, get ready to delve into the assorted types and applications of semi-crystalline thermoplastics.

Simply put, semi-crystalline is synonymous with strong. These polymers might be a bit more susceptible to a hammer blow or random drop than their amorphous cousins, but many are considered “engineering grade” materials. As a rule, they are very well-suited for use as wear surfaces and components that see high structural loads. And as you’ll see with many of the semi-crystalline materials we’re about to cover, they are resistant to solvents, as previously mentioned, which means that they also have excellent chemical resistance.

Along with all these desirable properties, however, come some drawbacks. That’s because all that hardness and tensile strength make them a bit more challenging to process. As our machinists at Prismier can tell you, plastics like Nylon and Delrin aren’t especially difficult to cut (although the latter is a bit smelly), but the folks in the plastic injection molding department might complain that semi-crystallines’ sharp melting point and “anisotropic flow” characteristics make them more challenging to mold.

None of this is a real problem—we handle these materials regularly—but you should be aware of potential impacts to the mold design, dimensional accuracy, and final piece price. Don’t let that dissuade you from considering these polymers for your next project, however, as semi-crystalline polymers positively rock in certain applications.

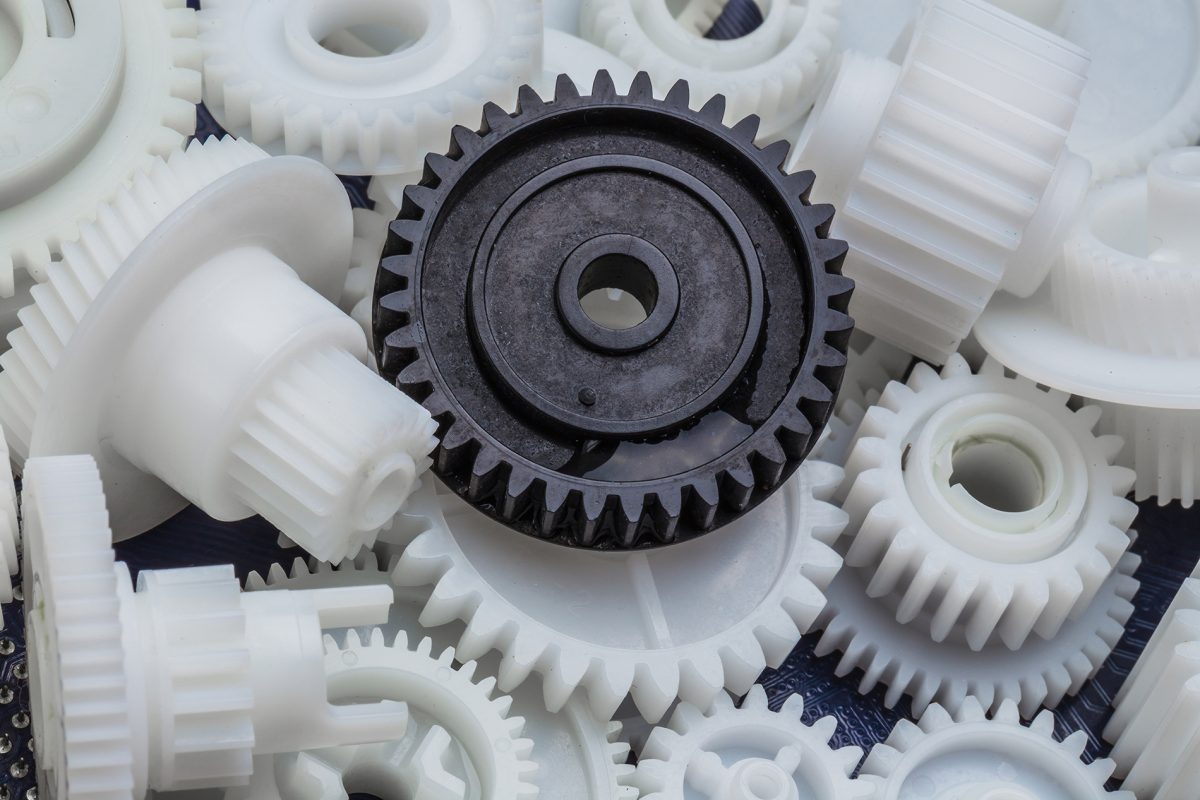

That said, PEEK and its 260 °C (500 °F) continuous service temperature rating and exceptional resistance to wear and fatigue, creep under heavy loads, and chemical attack (but not acids) make it an ideal choice for all manner of mechanical components. These include gears, pistons and valves, vacuum plates, electrical insulators, and a good deal more.

PEEK is a member of the polyaryletherketone (PAEK) clan. Its brothers are polyetherketone (PEK), polyetherketoneketone (PEKK), polyetheretherketoneketone (PEEKK) and the mouthful polyetherketoneetherketoneketone (PEKEKK). Though none have very original names, each is robust like PEEK and carries its own distinct properties. PEEK, however, is the star of the show, seeing broad use in the nuclear industry, chemical and food processing equipment, oil and gas extraction, and similarly demanding industries.

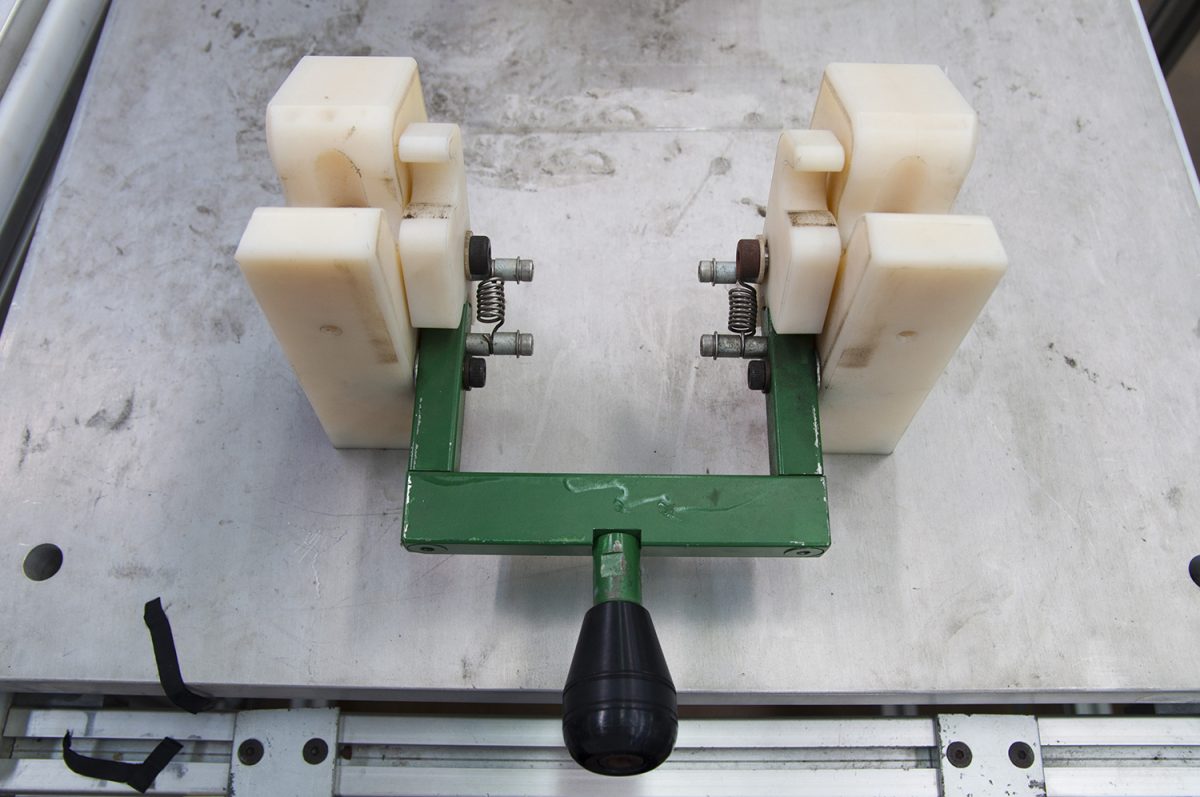

Delrin’s maker is DuPont, which claims it is “the ideal material in parts designed to replace metal.” Whatever the maker, acetal (or POM, if you prefer) offers many of the same properties as PEEK. It isn’t especially biocompatible, however, so you won’t find it inside the human body (although it is FDA approved), and its working temperature range is roughly half that of PEEK. Think industrial and automotive parts, jigs and fixtures, and any application requiring a strong, stiff, lubricious, and wear-resistant material suitable for both wet and dry environments. That’s acetal.

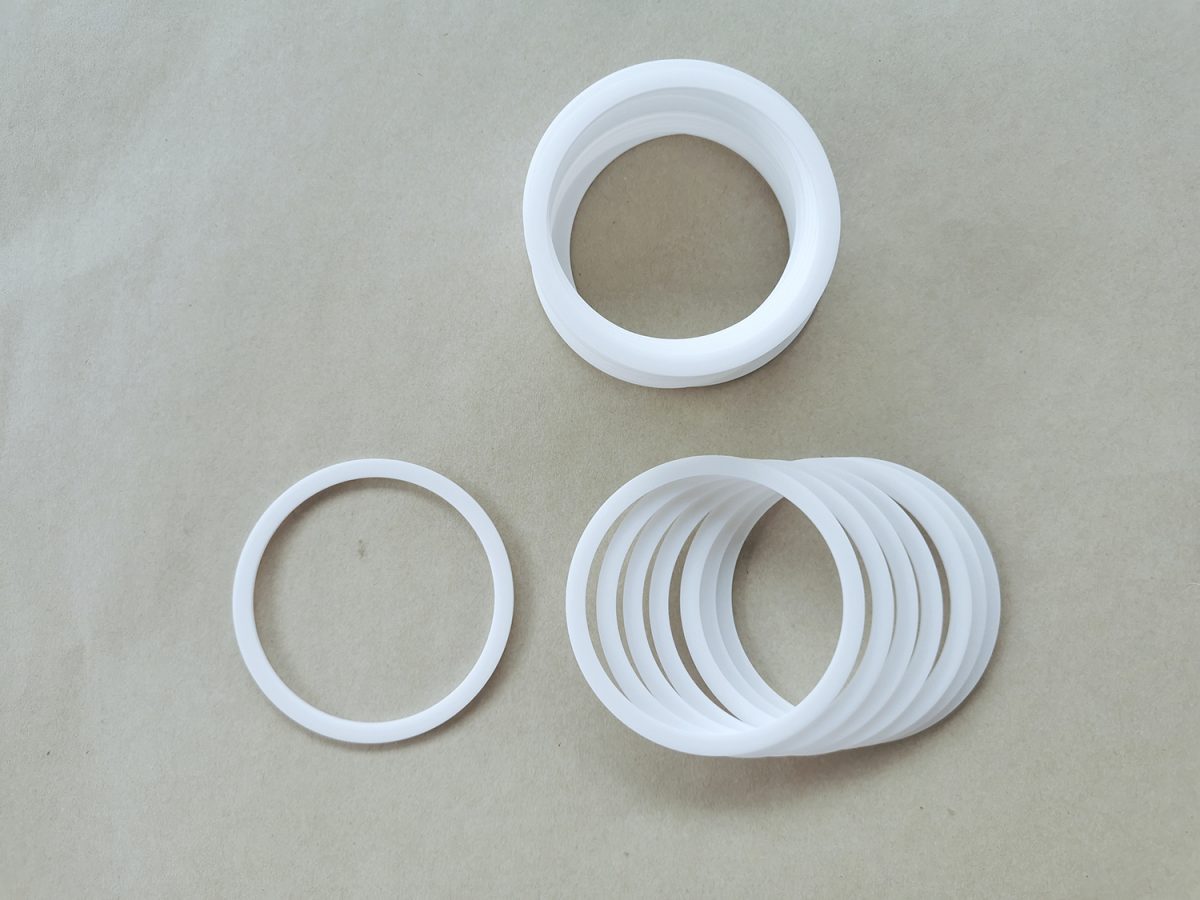

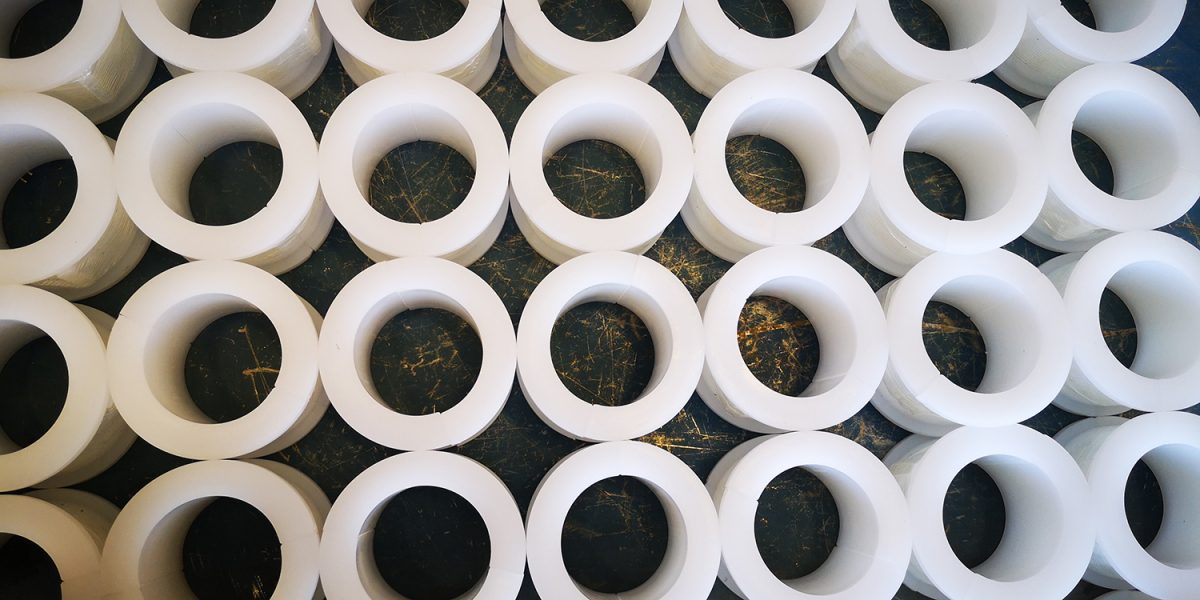

For such a soft, almost squishy material, PTFE has an exceptionally high melting point at 327 °C (621 °F). This attribute makes it practically impossible to injection mold, although it is readily machined and stamped. It does tend to creep under pressure, though, so if using Teflon as a load-bearing surface such as a washer, bearing, gasket, or seal, it should be mechanically constrained somehow.

Nylon is good for much more than oral hygiene, however. While Prismier doesn’t make tents or rope (two common uses of Nylon), we do produce all manner of injection molded parts. Nylon is often the first choice for sports and recreation equipment, automotive components, sprockets and gears, and similar parts that require a blend of high strength, toughness, and temperature resistance. These qualities can be further enhanced via mineral or glass fillers, while Nylon’s resistance to sunlight (it’s prone to cracking and “chalking”) gets a boost from UV blockers or stabilizers.

Let’s start with polypropylene, which falls into two distinct classes, homopolymer and copolymer. There’s no time for a full science class here; just know that the latter is softer but tougher, more impact-resistant, and unsuitable for food contact. The list of potential applications, however, is nearly identical.

Polypropylene is the top dog for products such as plastic lawn furniture, car bumpers and battery casings, kids’ ride toys, and packaging materials. It’s flexible and can be used to make living hinges (the tops of shampoo bottles, for instance). Thanks to its elasticity and chemical resistance, it often finds its way into containers for various liquids, such as cleaning agents. And because it’s also resistant to steam sterilization, PP is a favorite for many medical uses, including sutures.

Then there’s polyethylene. The online plastics database Omnexus states that more than 6,000 grades of PE are available. For those who are interested, it also dives into the chemical nitty-gritty of these two ubiquitous polymers, noting that PE falls into a handful of broad classes defined by its density—high-density polyethylene (HDPE), low-density polyethylene (LDPE), and so on. Regardless, the uses are many, and for anyone looking for a low-cost, easily processed, lightweight and durable polymer, PE or PP (and all their many variants) might very well fit the bill.

And thermoplastic polyimide (TPI) maker DuPont (which sells it under the brand name Vespel) claims that TPI is a “high-performance solution for the toughest sealing, wear, or friction challenges.” The polymer database mentioned earlier gives TPI equally high praise, calling it “one of the most heat resistant engineering thermoplastics available that can be melt-processed by injection molding with great precision.”

Then there’s PET, or polyethylene terephthalate, a notable relative of polyethylene. Most know PET as polyester, the stuff of stretchy pants, although it’s also found in electrical connectors and numerous automotive applications. Sharp-eyed Manufacturing Simplified Blog readers might have noticed that PET is listed in the Materials Monday: Amorphous Thermoplastics post referenced earlier, where it was described as a suitable (but amorphous) choice for soda bottles and peanut butter jars. What gives?

PET is one of those polymers that can exist in either state. Actually, there are many others as well. In fact, most polymers contain regions of both amorphous and semi-crystalline polymer arrangements, and based on their processing, are made to fall into one camp or the other. Don’t worry about it, though. What’s most important is to select the one that best meets your requirements, a task that the experts at Prismier are well-qualified to help with. Feel free to nudge us if you want to shoot the polymer breeze some more.

If you'd like to know more, pick up the phone and call us at (630) 592-4515 or email us at sales@prismier.com. Or if you're ready for a quote, email quotes@prismier.com. We'll be happy to discuss your options.