Quality

The Swiss Army Knife of Manufacturing

June 22, 2020

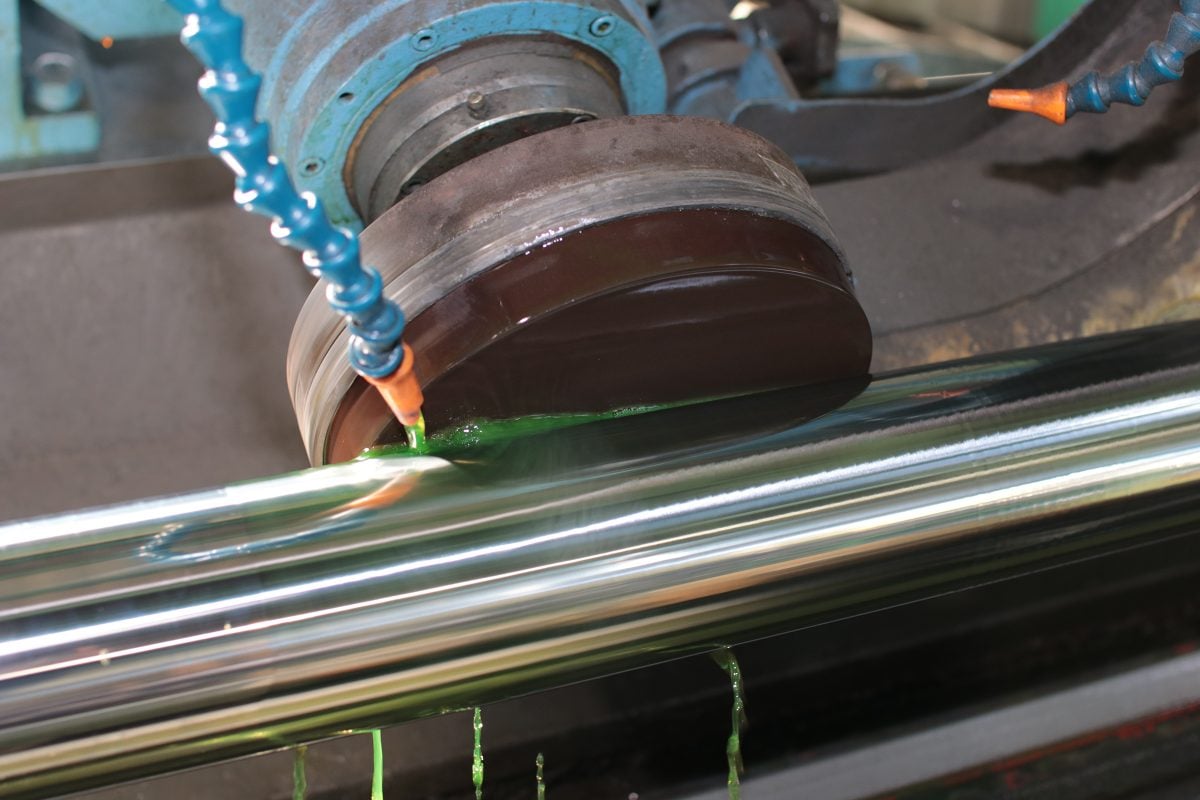

Commonly referred to as just “chrome,” chrome plating is a metal coating used to create a thin layer of chromium on the surface of a metal or plastic part. Chrome has long been a darling of the US automotive industry, with vintage cars sporting features like a shiny supercharger beneath the hood, massive exhaust pipes running down the sides, and big bright silver bumpers along the front and back. Hydraulic manufacturers also use chrome for cylinders, pistons, and various pump components. Textile producers and printing houses plate their press rollers with chrome, while die and mold shops use it to protect wear surfaces on tooling. Refrigerator door handles are chrome-plated, as are faucets for the kitchen and bath, boat propellers and ball bearings, musical instrument hardware, watches, rings, and bracelets.

Why is chrome plating so popular? For starters, it is both durable and hard, able to reach up to 70 on the Rockwell C scale. For more about hardness-testing methods, see this Hardness comparison table. It’s also quite resistant to corrosion and, above all, beautiful, bestowing a smooth, lustrous surface that’s easy to keep clean. That said, it ranks among the most expensive of all plating processes while also generating some waste products that must be carefully controlled and disposed of.

Chrome is a type of electroplating, a cousin to nickel plating and anodizing. If you’re among the enlightened group of people who read our Finishing Friday: Shine On post, you already know that electroplating requires the use of anodes and cathodes to send current through the workpiece while it hangs suspended in a heated chemical soup.

There’s much more to this process, however, one filled with terms like hydrogen embrittlement and substrate requirements and hexavalent baths, all of which can be found in ASTM B177 Standard Guide for Engineering Chromium Electroplating. But unless you are planning to open a House of Chrome or launch a “Chromes ‘R’ Us” online plating service, we suggest you save the small fee and ask the folks at Prismier for guidance on which plating process is right for your parts.

It’s this greater thickness level that also gives chrome plating the extreme hardness mentioned earlier—where the dining room cutlery you received at your wedding reception was decorative chrome plated (or possibly nickel plated), the stamping and forming dies used to make them were almost certainly hard chromed.

Before diving into a Cliff Notes version of the chrome plating process, let’s take a look at where chrome comes from. Simply put, chrome is chromium, or atomic number 24 on the periodic table, a silvery, metallic, and extremely hard element. It was first discovered in 1797 by Nicholas Louis Vauquelin, the French chemist who discovered the equally important metal beryllium one year later. In addition to chrome plating applications, it can be mixed with other metals to form stainless steel and other alloys, used to create pigments with vivid green, yellow, red and orange colors, and added as a main ingredient in the chrome tanning processing of leather and other fabrics.

In the case of chrome plating, the electrolytic bath is more than likely filled with a chromic acid solution (depending on the process and plating house) containing the inorganic compounds chromium sulfate or chromium chloride. If you need the gritty details, check out the Chromium Plating for Engineering Applications course at the National Association for Surface Finishing (NASF).

Of course, chrome plating is often applied over other electroplated surfaces. Some plating houses might first apply a thin layer, or pre-treatment, of copper, followed by nickel, sometimes referred to as a strike, and then chrome on top. Between each of these steps, a thorough clean and rinse is required. Chrome-plated parts must also be very smooth and blemish-free before beginning the process, as any ugly spots will be even uglier once they are removed from the tank.

It’s also important to note, especially in this car bumper example, that old, tired chrome plating can be stripped off and the part re-plated. In this case, the steps are quite elaborate and the required expertise level much higher. In some cases, it may be preferable to machine, stamp, or fabricate parts fresh from the production floor to avoid that complexity. Chrome is also used to build up worn part surfaces, which can then be re-ground or lapped and polished to size.

There’s plenty more to this story. If you’d like to talk about electrolytic metal plating or any other manufacturing topic (or even vintage cars) give us a call. We like parts.

If you'd like to know more, pick up the phone and call us at (630) 592-4515 or email us at sales@prismier.com. Or if you're ready for a quote, email quotes@prismier.com. We'll be happy to discuss your options.